This is part 4 in a multi-part series.

On the morning of Stella’s birth we were ready.

With Charlotte’s birth, 5 ½ years earlier, we’d prepared some … Hans and Amy, 28 and 35 respectively, actors, moderately good partiers, sometimes living hard … but we weren’t really ready for what came after the birth. We’d learned from Amy’s mother to avoid the typical western birthing route, been to our midwife’s office several times and made day-of plans; we had the inflatable pool ready to be filled with hot water by the time contractions started. And three hours after Amy drenched a movie theatre seat with fluid, and a fast car ride home, the sweet baby Charlotte was born underwater in the living room of our small Rainier Beach house. Afterward, surrounded by friends, we were able to stay put, eat a comforting meal of Thai food, laugh at the miracle of birth with our friends and stare at the new beautiful gem of a human: Charlotte Francesca Thone.

We did NOT, however, have diapers in the house, or a crib (not that we ever used one) nor had we prepared for the first night when we discovered she was still learning to breathe properly. In general, we had no idea what to do. It was an alarming experience, beautiful, life-affirming, but startling.

When Stella was due, we had it all planned, all of it. We’d raised Charlotte and done a solid job not breaking her (though I did try a few times accidentally). The house was calm and we were stocked with baby goods and we’d secured the services of the best midwife in the PNW. Amy’s body, on the other hand, was not ready when the clock was up and Stella was ready to come out. Trying to stay active and positive, we waddled to the car and drove to breakfast at Geraldine’s in Columbia City, an extra towel under our arms, just in case. Sitting in the second to last booth on the south side of the Columbia City anchor business, leaning against the bricks, just down the block from our midwife’s office, we ate our food and pretended nothing amazing was about to happen. Gary, the proprietor of Geraldine’s, had approached his regulars and said hello like usual and then asked what the towel was for.

His face when we told him … host with the most … unforgettable. ‘You mean, it could happen right here in this booth?’

Later, after walking east up the street to the Seattle Home Maternity Service office to visit with Marge Mansfield (lucky us) and make a final plan for the day, we got in the car and headed toward home again; the car ride having produced nothing new, we took a walk with Marge and our friend Selah, (lucky us), down to Pritchard beach before deciding it was time to go back to the house, where Marge would have to break the water herself. It was past time.

The pregnancy had been very difficult. Amy spent months on the couch in intense discomfort and nausea. We prophesied that the pain and difficulty was due to the fact that we were having a boy and that he was fighting Amy’s body. We’d even picked a name: Milo.

Baby G Altwies, later named Stella Blue Summer Altwies, came out screaming her head off along with Amy, whose nails must still have my DNA under them. Pinned against our living room wall by Amy leaning hard against me, I was confident it would all go well with Marge as our guide; and Selah and Brad nearby, Charlotte was ushered upstairs by Joel to avoid the screaming and sit on the landing to listen … and wait.

Marge did her job but the water was cloudy with meconium. Marge reminded us even if the baby seemed ok, by law, we needed to monitor her level of aspiration in a hospital setting and that meant making the call. I didn’t move … I guess I still felt save, if not physically pinned.

As soon as Stella’s head emerged, Marge immediately did what she should have done. It wasn’t trauma, but she needed to make sure Stella didn’t inhale too much of the wrong fluid, so she kind of attacked the little wiggler with the suction bulb, placing it at her nostrils and pulling, several times, producing higher levels of screaming. Marge did this with a serene look on her face and calm hands … of course. Stella was still mostly inside Amy, just her pink little head sticking out. Her first breath was … well, abrupt … and I didn’t like it … she entered the world startled. My body took this on, I was now nervous.

Years later I wondered how different Stella would have been, if at all, had she been born underwater, a purple frog-looking creature, like Char; she’d floated under water for a good 10-15 seconds before I’d pulled her up to the surface; once there, I’d turned her face up, where she opened her eyes for the first time and then on her own, took her first breath.

My theory is we are all 87% nature, 13% nurture. Notwithstanding my blindness in that privileged theory, I’m curious about Stella’s first moment on earth. How much did her nature deflect or harbor the intensity of the physical task of suction at her nose at the instant she took her first breath? To what level, if any, did it affect her feeling of calm or safety as she grew? She was scared of so much as a kid … was it that moment? Or was she that way already? She was also inherently helpful … did that action carry with it a lesson of usefulness she held onto?

Marge looked up at me and said, ‘we need to call, it’s not too much but she’s aspirated some and we have to call.’

We dialed 911.

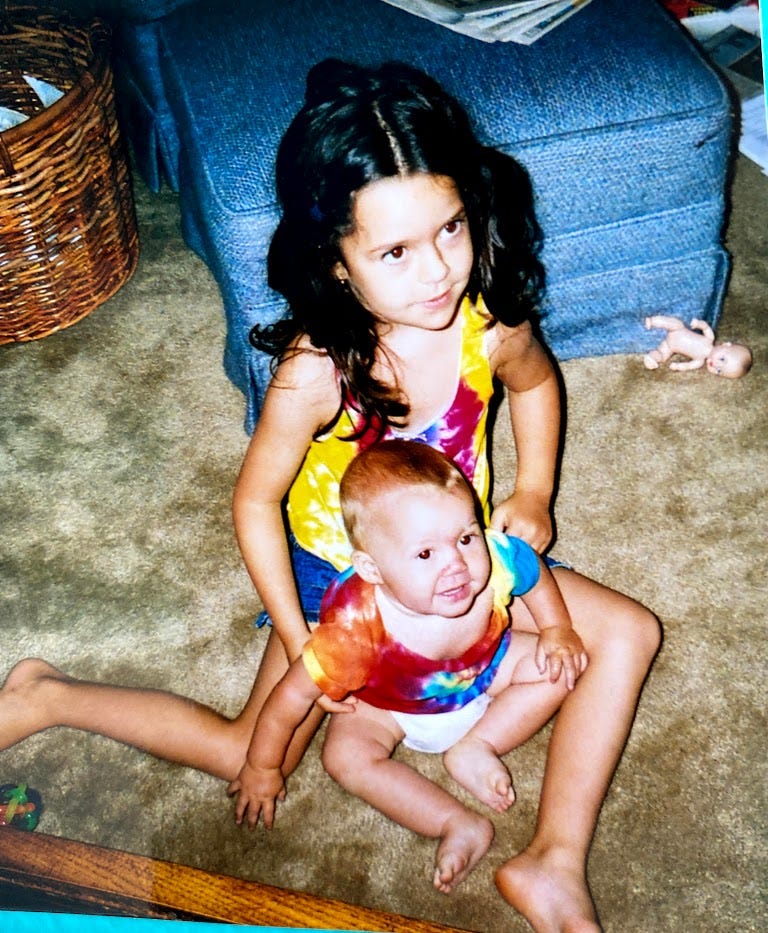

Stella came all the way out with house-vibrating screams (topped only by her mother’s screams), a perfect little baby, red marks on her head and nose that would stay for years. Charlotte, who’d come downstairs as soon as Joel had let her, stared at her new sister. (I still think she was ushered upstairs, away from the birth, more for Joel than her). When Marge asked her if she’d like the privilege of separating her sister from her mother, she cut the cord herself with the scissors, a confident and stern look on her little face, her first act of being a big sister.

The quiet smiling firemen/women arrived 5 minutes later, standing with their arms behind their backs, beaming down at the healthy baby, no doubt comforted by Marge’s deep calm and understating of the situation. Amy had to stay behind for more doses of pain from Marge’s needle while I was blessed with the best trip in an ambulance anyone could ever have. I was aware what was happening behind me as we pulled out of the driveway with the sirens wailing, me lying on the stretcher with the little peanut resting on my chest, but I was far more focused on my prize than I was worried about Amy; she was safe, even if now dealing with the secondary pain.

Rush hour in an ambulance, 10 miles from South to North, infant lying on my bare chest wrapped in mylar to stay warm.

Oh, that trip.

Right then we were bonded … to have this alone time, to hold and love my new daughter, the first person in her life to hold her in a long slow embrace … it was a moment equaled only by Charlotte’s magnificent first night at home; I savored it in the moment just as years before, I’d savored my private rocking chair moment upstairs in the old attic/bedroom an hour after Char’s first meal. Never has mylar felt so good; I wanted to stay there forever. She slept. I melted.

When we arrived at Seattle Children’s Hospital’s back door to the ER, having weaved through Seattle’s not-horrible-enough, Northbound I-5 traffic like king and princess of the city, I carried her into the intake area smiling like a fool. They instructed me to lay her on the raised table in the first room I entered; the meal table was heated from above by a red lamp; it was like a diner plating station … little hot dog.

Nurses and doctors crowded in to see her: 5 or 6 of them, not attending us, just curious, stood around us with beaming faces, to look at the little, healthy newborn girl with rosacea on her brow and nose, their arms behind their backs.

Perfect.

That day first responders peered at our girl and welcomed her with smiling faces. She spent the rest of her life trying to draw smiles from everyone she ever met.

The nurses in NICU called her well-baby Altwies and on the report at her bed it read only: Baby G Altwies. We were still surprised she was a girl and we hadn’t named her yet.

She never had anything close to dangerous levels of meconium in her lungs and her stay unfolded without incident.

She was discharged 3 days later.

Before we left the hospital to make the 10 mile ambulance ride back home, Stella Blue, Amy and I had a conversation about things that might make her feel better, things that might take her mind off dying. We were in her Ocean 8 room, sitting on either side of her bed of pain willing her to find some joy. She started by saying ‘I just want something to be pleasurable’ and we perked up and leaned in. We worked through an extensive list together and landed, first, on cream puffs, the kind you get at Costco and then the winner, the comfort she could come up with that sounded truly pleasurable: ‘I want to hold a puppy’.

All day she’d repeated through her screen of drugs, ’I want to go home.’ We’d decided along with the doctors that there was no more benefit from either radiation treatment at UW, nor the hospital care she was receiving at SCH. After painful reasoning, a few brief training sessions and extensive logistical blabbering by the patient palliative and Hospice team explaining our next steps, Stella Blue left the building at 6pm, February 4th, 2020, 14 years and 3 1/2 months after she first visited the large concrete building.

On the ride back home, (endless, we couldn’t wait to be out of the ambulance), upon Amy’s request (she couldn’t do it herself because she was hovering over Stella unable to see out the window), Stella was told what building or park we were passing as we drove through the city. Stella loved tracking the landmarks … and the young EMT, who sat in the back with Amy, didn’t flinch at the suggestion, looking out the back window, calling out names of neighborhoods and landmarks all the way home until we pulled onto our street.

The van backed up the steep drive - the same one I’d pulled various cars and pick-ups into for years; the one I’d directed dump trucks to dump gravel in and dirt for our constant home improvement projects; where I’d watched as lumber trucks scraped their bottoms trying to get past the steep hump to spill their lumber in my drive; where the girls made pictures with chalk on the broken asphalt, rolled down it in their yellow and red, Little Tikes Cosey Coup plastic car, chased hundreds of rolling balls down it into the street, and where Stella had stood, legs spread, 1 year earlier, bow stretched taught and loosed an arrow into a straw bale at the garage.

I never imagined an ambulance with such a package pulling into this home.

It felt like a dream, like someone else was acting out this moment of defeat and finality: our daughter was coming home to die of complications from cancer…a phrase we couldn’t have imagined until we peripherally considered it was possible seven days earlier when Stella asked: ‘How do people die from cancer?’ The reality of it though, standing in the driveway as the EMT opened the back of the vehicle, seeing Stella there in the stretcher, arms on her chest, with Amy next to her, made for an out-of-body experience.

How did we get here? How is this happening? Who is this family?

We pulled the stretcher out and onto the driveway. It was dark by now…or gloaming at least, but there was enough light from the garage can lights that we could all see what we were doing. Alex, our next-door neighbor, walked up his front walk holding a bag from his day’s work; he paused and said ‘hi’, awkwardly and warmly when I looked over at him, and then he went up onto his porch where he turned and stood still to watch us.

We wheeled her up the walk, past the King’s table and our once-busy front yard to the porch, with Amy going inside first to clear the path. Kaleo was there waiting maybe, I don’t remember, others though I can’t remember who, someone was probably there … my mother for sure. Getting her up the steps was trickier than I’d expected with the two younger EMT’s … it was just heavy…surprisingly so. Stella was sweet the whole time, with her arms crossed on her chest like a good Waldorfian.

Inside the house, in the entryway, we showed her the bed Kaleo had set up in the living room under the large skylight in case she wanted to be in the middle of the action. The answer was quickly, ‘no’, she wanted her own bedroom, her own place; we weren’t surprised, and in hindsight it would have been a terrible sprawling, a public space, when what we needed was the quiet, dark environment of her bedroom.

I picked her frail body up off the stretcher and stepped into the living room. I felt a certain ceremony envelope us as we moved into the dining room/play room/sometimes living room off the kitchen, the one she’d made art in, played endless games in with her family, rolled around in…it was probably residual theatre sap still attached to me but I must have slowed down to feel it…it was overwhelming knowing she’d never come down here again alive…or would she?

‘Go quicker, just walk faster’ she said ... and I did.

Up the stairs past the American Girl Doll’s hideaway, also known as the Anette Toutanghi memorial sleepover space, past the plant landing, up the second rise of steps and through the Lego hallway, into her bedroom and her excellent bed where I lay her down with the feeling I’d just delivered her a powerful pain medication: she visibly sank into comfort.

She was finally home, home for good.

The stillness didn’t last long. She kept her promise and got up to take a long-awaited shower. We helped her to a standing position and slowly hobbled out into the hallway and then into the waiting shower. Her gate was awkward; we didn’t understand what hurt or where exactly (like we did a week earlier, when we thought our daughter was complaining out of fear … oh we felt terrible about that); the jerky movement and weight on her bones required her to drape her arm over our shoulders and we triaged her into the bathroom.

It was the last time she ever left her room, I think.

It wasn’t a very useful shower to be clear. ‘Nope, nope, I’m done’, she said loudly after 15 seconds in the shower. She was afraid of getting the stickers on her right cheek wet, her leg hurt, nothing in her wanted a full soaking shower; we bailed. But…spirit … trying … I was so proud of her … silly that was what brought up such an emotion, but true … a winning effort to prove just how grateful she was to be home.

We, on the other hand, were terrified. What were we supposed to do tonight … or the next few days, weeks? How do we suddenly take care of our dying child with no doctor or nurses to constantly check on us? Our dear friend’s sister, a hospice nurse from Bellingham, was spending the night in our bedroom, to get us started; we would sleep in Stella’s room with her. But more than helping us sort through the drugs and how to administer them, it was the comfort of having her experience nearby that soothed us that night.

Back in her room Stella finally let go and after gathering her favorite stuffy, her daemon cat Spunky, favorite pillow and favorite blanket, fell sound asleep. She slept deeply for hours without the constant buzzing hospital atmosphere to jar her awake; the iv pushes beeping ‘empty’, the sweet but constant hospital peeps coming in and out of her room to check on her, delivering all her meds.

She was home.

By midnight Amy and I were exhausted as well and collapsed on the bed around her.

We all slept hard that night.

Amy and I woke early on February 5th, Amy lying next to Stella and myself wrapped around their feet at the foot of the bed.

Friends were gathering downstairs. Kaleo and Kathy, Billie, Josh, Jessica, Makaela, Brad and Joel. My mother was still with us, of course, bustling about, making the world turn. Except when she was stock still, right hand draped over left, elbows tucked, staring at Stella, or Amy or me. My Brother was going to join us soon, and Kristine, Ava and my dad would be coming too.

I was sitting with Stella while she slowly returned from 13 hours of mostly undisturbed sleep on her first, full day home; I cooed to her, trying to pull her up and out of her deep deep stupor, toward me, and nearer to consciousness; selfish of course.

‘Hey Stell Bell, do you want to wake up?’ I wanted her conscious, I didn’t want her to fade away back into sleep…so I asked another question.

‘Do you remember what you said in the hospital the other day? About wanting us to finish the things you started. What did you mean by that?’

‘Shush’.

Right, got it. She shushes us often and it’s good enough for me; she’s still right there. As much as I long to know what she wants us to do for her when she’s gone, as much as I desperately want her to make some grand statement of her legacy, like, ‘please start a foundation for such and such,’ it’s not going to happen, it’s not her job, that’s the movie.

Shush indeed, dad; she was deep inside working through all of her very pressing tasks at hand: trying to keep the nausea at bay, calming herself. Who knows if she was processing her life, contemplating her feelings about death.

God, what was my daughter thinking then?

Amy and I just waited for the openings, for the sudden comments she came out with.

I sat and stared at her lying there; her left arm on her stomach, Spunky lying against her side, her right hand on the PCA (patient-controlled analgesia) she could trigger for a morphine shot if she wanted. She was floating away on morphine already.

Still leaning in, unable to walk away, I told her it was time for some THC:CBD tincture. She needed to wake up … needed? I wanted her awake.

‘Ok, it’s time for your medicine. Open up, just a couple drops’, I said holding the vile ready.

‘I don’t like drugs that put me to sleep; I want to be awake.’

‘I know. This is THC, it will help you feel just a bit happier…maybe.’

‘Uhh’. It was her short grunt, back of the throat, quick. It meant no. I put the small brown bottle down after dropping the contents under my own tongue. ‘It helps me, Stella, it would help you too’, I wanted to say again. I didn’t.

She was mad, disappointed, though not visibly. She knew (I believe) there was no one to be mad at in particular; but she was still really, really pissed at all the pain and nausea she had to carry with her to the end, and she was pissed at losing her brilliant 14-year-old self. Her rapid descent toward the other side hadn’t given her time to process anything … it happened so very fast.

Later that day she said:

‘I know I’m not supposed to sleep all day, but...I also just want to sleep.’ She said this with just a hint of her old smile.

She wanted to be up for the party called life, but she could not break through the morphine fog for long. ‘Here, let me get you stoned on morphine and THC, daughter,’ it was all backward logic, confusing and hopeless, but we took the steps we needed to keep her out of pain.

I wrote back then: Stella can hear better than seems possible and her vision is going, we think … we can’t tell because she never opens her eyes; and she can think at full speed, faster than she used to even, more clearly it seems. But her body doesn’t work anymore; she can’t sit up without help; she’s getting thinner, her little arms softer, and her whole body has slightly dry skin...little Anna’s hummingbird. She mostly lies on her back with her arms crossed on her chest looking like an angel and flowing between a shallow sleep and almost awake.

Today, April 23rd 2023, reading those words, I feel removed. I want 10,000 times the words to help me get back there, to know BETTER what it feels like to hold that right hand hers, and whisper in her ear, and hear her shush me. And I’m still not sure putting my memories into words diminishes or brightens the mental images I have when I close my eyes and reach for her, but I don’t have another play; I’m constantly afraid of losing the little I have.

Thank you for bravely sharing your tender Stella-ness... love you.

Thank you for opening my heart today with this life and death story.