This is the third installment in a multi-part series.

By February 2nd, 2020, Stella Blue was moving further and further away from us, down inside herself to a place far away where I believed she was consolidating her strength. One glance at her if you walked in the room on these days, was enough to see that something new was happening. I imagined, as I stared at her sleeping face, that her native body intelligence was guiding her inward, calmly and with confidence; her energy and larger than life spirit, sinking, not away, she was still there, but deeper, closer to her core.

The pain and drama of the previous day was behind her; and it was clear we’d now entered a new stage of her death … it all felt heavier.

This is a memory of a memory … with insight, ie. a typical memory.

She spent most of the first half of February 2nd, with her eyes closed, hands clasped over her chest or on her tummy, dozing, trying to stay away from the beeping machines and anything else that reminded her of her sickness in the room. I do it sometimes when I wake too early in the morning … when I want to stay half asleep, away but also not unconscious. Barbi does it when she’s stirring in the mornings, trying to remember her dreams: ‘stay away world I’m gathering the necessaries for the day’.

I also think Stella knew already, instinctively, that the cancer was back, and maybe not only in her hip; it was her after all who’d mentioned it days earlier. She may have even known there was darkness coming, bigger than just another location of the cancer. She was hiding, fight or flight, but with high-level young person ease and bravery in the face of the unknown, waiting, until we were ready to speak.

This is a long-game new understanding guess.

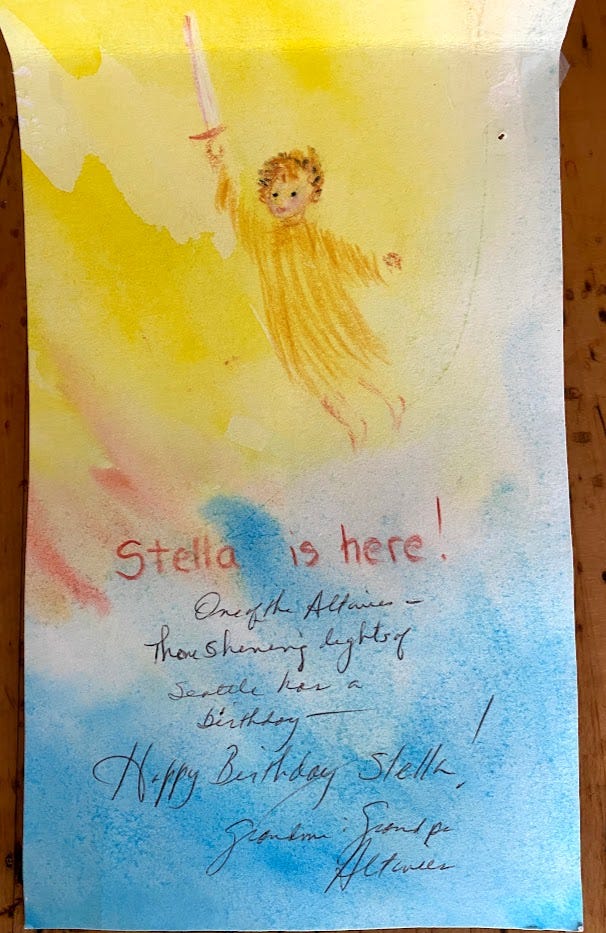

If she could be rendered sentient - just as she was, lying still in her bed, with her mother and father near her, leaning forward toward her - in a Waldorf painting, produced by a magic 5th grader of impossible talent, it would look like this.

A gorgeous, still teenage girl with a glowing golden light coming from her center, captures the middle of the painting, your focus begins and ends there on the slip of a girl you immediately love. It’s a very dark painting…mostly blues a zillion shades, all deep and heavy … and an exquisitely detailed one as well; though there are no hard lines, an infinite number of feelings and items are visible to you: curtains, machines, chairs, Amy’s twinkle lights, her stuffies, her boo, her uneasiness, the parents sorrow, the recent history of the room … everything there, yet all subtle and giving focus to the figure. There lies a young woman, beautiful face, mouth slightly open, with softened features; you may even catch a movement, if you breathe slowly and focus, a small sigh, in and out, a tiny turn of her sleeping head. Oh that Stella Blue!

And that golden, glowing center in her chest radiates. Golden, then deep oranges and then reds and purples and then the blues and greens. Standing above our girl, barely visible but for their very brief color - a color lit by the strength of hers, their dimmed but struggling life’s color - you see the darkened shadows of her parents hovering over her bed. Their own sense of dread, noticeable by their fierce gazing at our hero, shrinks and grows like slow, unsynchronized heartbeats. And in this moving picture, changing in every instant along with her, that center, that core light is getting brighter … and smaller at the same time; smaller and brighter, brighter and smaller. And her figure grows and the parents’ figures diminish, the painting pulling you in toward her. It’s a comforting embrace. The rest of her body, blue’s and purples and shadows, is becoming non-essential to her; her universe, now connected to something beyond, becoming a glowing memory; short but blazing with everything that ever was.

A feeling memory.

So while she lay there not sleeping with her eyes closed, in the moments of silence between doctors, nurses and talking to friends; when Amy and I were alone … in the in between moments, I stared at her, tormenting myself about our secret.

I was getting frustrated; Amy and I were still at an impasse and she was not budging. It wasn’t new stuff for us, we’d been at an impasse for years. We were excellent partners in life, with typical cracks in the armor. Unfortunately for both of us, there was no intimacy we could trust in and there was little tolerance for anything outside our lane of operation. We were good at being co-parents; we were good at being friends to our friends as a team; and we were great at being nurses, at keeping our tag-team of attention on Stella free of anything petty.

But this was testing us.

We stared hard at each other across Stella’s sleeping body late in the morning on February 2nd, the room dark and the beeping of machines ever present. Amy was holding Stella’s hand, her eyes now closed too, her head tilted back with almost a smile on her face … this was her coping posture: getting through, her way of staving off collapse. That’s what it looked like from the outside; I don’t know exactly what was going on on the inside.

So much unknown.

Here was the rub: I wanted to tell Stella Blue the truth, that the cancer was back and she was going to die. Amy said no, we couldn’t tell her yet.

We’d known now for 7 days.

‘It’s not our choice to keep this from her, she has to know’, I said.

‘Absolutely not’, she said.

‘It’s not fair, she needs to know so she can take the next step.’

‘No.’

I felt sure that our omission, as large as the sun, was a terrible vice grip keeping her from beginning the journey forward, holding her back from her own first stage of grieving … and maybe even relief, though I didn’t have the knowledge or learning to back that up; to me she couldn’t move into acceptance and the awareness that might follow. For Amy it was simply impossible…why on earth would a mother want to share the news with her daughter, her sweet, innocent, beautiful youngest daughter that the end was upon her. And there was so much we didn’t know: how she would die, when, what it would feel like for her, what we would even be addressing as far as pain. We had no idea what was about to happen.

‘You don’t know what you’re talking about…just wait, I’m not ready’, she said quietly to me.

Well, she was right, two times over: I didn’t know what I was talking about – I was guessing…grasping for the truth – and the end had arrived staggeringly fast and without warning and … neither of us were ready.

How do you get ready for this?

Where’s the rulebook for this moment?

After a short hot conversation, hushed and hard, both of us desperately hoping that Stella couldn’t hear through the heavy load of pharmaceuticals, I had to leave the room. I had to go sit with our loving posse in the lounge, I needed new sounding boards, my friends, where they all waited with huge eyes for any news, waiting for a moment to look at us and pull out the pain with their will. Or, most coveted of all, catch a scarce invitation to go see Stella. (This was another struggle of ours; I wanted people in the room; Amy was protecting her daughter’s energy so we rarely invited people in).

I pulled Steph aside and whisper-yelled that we were making a mistake not telling Stella. I was sure we needed to tell her. But, I was betraying Amy and putting Steph in a terrible position by trying to convince her of something only Amy and I could decide, so I shut up and sat down and stared out the window at the beautiful outdoor garden we weren’t allowed to walk around in.

I loved being mad about that.

‘Why build a beautiful rooftop garden for the sole purpose of giving a grieving family a place to walk around in a beautiful rooftop garden and then close off the beautiful rooftop garden for more than a year?’ So fun … see? It had been closed since April of the year before, when we were first here.

But I had something else that drew my focus back, away from the fun of being mad about nothing.

Stella Blue, what’s going on in her head? I sat there fuming, imagining Stella lying in her room, eyes closed, not sleeping, having conversations with herself:

‘Why am I up here in ocean 8? I must be in trouble. Maybe I’m dying … of course, I’m dying. Why aren’t they telling me…I can take it? What’s happening?’ Guessing her thoughts became a kind of torture. I told myself I was looking for something to make myself feel better by picking a fight with Amy. I also told myself I was right.

‘She knows, I know she does’, I said to Steph, again. ‘She’s waiting for us to tell her so she can confirm what she already knows and move on; by not telling her we’re creating confusion, we’re abandoning her … we have to tell her.’ It was so clear to me… I think I used the word ‘gift’ when preaching to those converted friends; ‘telling her is the only gift we can give her’. Uggh. But what could they do about it; what power did they have? Only to nod their heads and tell me they understood.

They told me to sit down again. ‘We brought you some food, you need to eat something’. Or they raised themselves toward a potential hug…. I didn’t feel like hugging most of the time.

For Amy, back in the room, I’m sure it was torture heaped upon torture, and I could feel it behind my own self-righteous anger; her husband was starting to push harder and harder to do the unthinkable and in the back of her mind she knew we needed to do so…at some point, but ‘it’s not the time, wait!’

So, we waited.

Later in the day Kaleo Quenzer, my friend since high school, big brother to so many people, Kathy his wife and my marathon partner, Maile, half a year older than Stella and in the middle of her freshman year of high school, all sat with Amy, Charlotte and I in the room facing the TV. They were our second family, our spend-every-evening together family. It was Super Bowl Sunday, a day usually spent at their house; the day we gathered if the Seahawks were playing or not. Here in the hospital, we sat in the room with the Q’s on impossible day number 7, watching the game with the volume low; we didn’t know if Stella was with us or not. As usual her eyes were closed. We didn’t know how high or low to keep the volume. We hoped it was comfort to hear it. We didn’t know for sure either way, though. Maybe it made her feel like the world was going on without her. Maybe it made her feel like the world was going on as usual … in a good way.

I sat on her left looking at her as she lay still, eyes closed.

‘Stop staring at me’, she whispered to me.

‘Sorry’, I said. And then told her I’d be staring at her and kissing her a lot in the coming days and weeks … and I remember (very clearly) trying to take back the words as they hit the air. ‘Why a lot in the coming days and weeks, Dad?’ she might have said … she did’t, she lay there quietly as I stared at her with slightly startled eyes. It was definitely a slip … I remember as the words were coming out of my mouth I was already thinking of a way to fix what might be coming. Luckily she didn’t catch it … or did and decided to let it slide. Maybe she didn’t want to deal with it. Maybe she was waiting for us to stand up and tell her properly. I don’t know. But she was so sharp … I don’t think she missed it.

Just watch the game, Hans. Make football small talk about the kid Patrick Mahomes, Pat Magroin as Kaleo calls him; listen to Charlotte crack jokes about Jimmy Gorappolo’s handsome but too symmetrical face. We didn’t know what else to do.

Movies were losing their interest and opening her eyes let in more light than she could process. She loved her sister to be in the room with her and hearing her friends’ voices over her bed as she lay there. She engaged sometimes but was often too sleepy to have full conversations. She heard everything even while asleep, we’d noticed in the past few days.

On this day with her framily, the Quen-th-wies’ all gathered, half-watching the least important game of any sport ever played, she was only half awake. At one point she stirred from one of her long stillnesses.

As we all sat silently, not caring. She moved her head, cracked her eye lids, watched the punt and then closed her eyes again.

‘Good field position’, she said, she was dead on…it was a terrible punt. Great for Kansas City, late in the game. Sharp as a sushi knife.

The day wore on, the game ended, the Q’s went home. It was just the 4 of us again.

I was squirming all day, through the game, now, sitting alone. I wasn’t the one in the relationship who could make big decisions about our children alone. I was the dad, less effective overall (I would somewhat agree with this) and Amy was usually dead on with her instincts. More than that, though, I allowed myself to be controlled and Amy had a hard time with collaboration.

I believe it finally went down like this: my memory of the moment, written down more than a year ago, two? More?

Stella was awake chatting quietly with Charlotte at her bedside, I’d said goodbye to the Q’s outside by the lounge, Amy was putting the room back together and it seemed like yet another opportunity to tell Stella the truth was slipping by. I stared balefully at Amy as I sat in the chair by her bed, and she moved around the room avoiding my gaze. Together we tried to decide if we should give her another ben-reg or Ativan – it was time for the next dose – ‘or wait and talk to her first, before she drifted off into the soft world of her waking dreams?’ I thought … willing Amy to see me thinking. Nothing. I kept trying to grab Amy’s attention without saying anything obvious, but she wouldn’t engage about it and the nurses came in and gave her the pills and there it went. It seemed the decision was made without discussion, again.

Then, after the nurses left, we were all gathered around Stella’s bed, and suddenly, it was time.

I don’t know what came first; the stillness and the obviousness of the time? Stella was awake, Charlotte was there. Or that Amy knew, and had decided she was going to tell her after the game.

I knew it was happening because I know Amy. She didn’t say, ‘Ok Hans, I’m ready now’. She didn’t look at me and acknowledge she was ready. She just leaned forward, dropped her elbows to her knees and lifted her chin slightly, eyes closed, she took a breath; it was her entrance move here.

‘We need to talk to you Stella,’

‘What?’ through closed eyes.

Then, with what we must have known she’d follow: ‘Am I going to die?’

Of course, she knew.

Simultaneously Amy and I answered.

This I know.

Amy: ‘maybe.’

Hans: ‘yes.’

It wasn’t a race, but both voices made it to her at the same moment.

Maybe. Yes.

We watched our daughter’s face break and she dissolved, a full body sob as the words crashed through her. Charlotte held her hand from her side of the bed and silently wept. Amy touched her face and I held her leg.

How would you feel if someone said you were going to die?

The three of us sat there wanting to leap inside her and clear away the grief and fear wherever it resided inside her little body, just scrub it off her bones and eat it and make it vanish. Instead, we sat there having delivered the mortal news ourselves, feeling dumb, cruel and useless.

‘How? Where is it?’

‘It’s in your pelvis and other places too. They can’t stop it, honey.’

But Stella came right back out of her terror with ferocious bargaining.

‘Tell them to cut off my legs, I don’t need them, tell them to do whatever they have to. I just don’t want to die.’

‘They can’t do that, sweet girl, it won’t work.’

I don’t remember who said those words, Amy or me … or if they’re the right ones.

She cried some more. Deep, deep sobs.

Then she spoke the tearful words I believe haunt Amy the most: ‘I just don’t want to leave you guys.’

All her days were spent with us; all her trust, love and strength started at home with us. We were the protectors who had failed to protect her but not for one moment, was she without love and devotion to us. Because she knew the same was true in the other direction.

And not a minute later she was taking care of the people she loved.

‘Someone has to tell my class,’ followed by, ‘it needs to be Mrs. Chamberlain.’

Then, ‘You have to finish what I started.’

But all of these first thoughts of hers after learning of her mortality describe our daughter.

‘Someone has to tell my class.’

It’s a simple sentiment but it cannot be spoken in a moment of reckoning, one like Stella just experienced, by someone who doesn’t hold the hearts of others side by side with their own; not in front or behind … just equal. This child was all love for her fellow man and her instinct was protection and inclusion and there was no question her peers needed to know. Because she knew. She could feel herself sitting in the classroom with them and imagine them not knowing and it was not an option.

‘It has to be Ms. Chamberlain.’

Another simple statement that shows the judgment, the clarity of what’s right and I’ll attribute this both to Stella Blue and to the Waldorf education that she was lucky enough to enjoy. The rules of living rightly are ingrained in the daily ritual of the Steiner education. One of these tenants, I believe, is the basic hierarchy of knowledge and from whom the knowledge should come; it is all about the fostering of the soul’s within each person and each of those souls takes a long time to bloom and a keen eye to garden them. The curriculum is the soil that holds these seeds of future adults, and that soil must have just the right chemistry. The teachers are the gardeners. And certain teachers have the experience, character and touch to till the small child patch well.

Ms. Chamberlain was such a teacher and Stella knew this. As much as she loved her mother or me or respected Dr. Ghoash, the head of school, it was the only choice: Ms. Chamberlain would stand in front of that class and speak the words that would change the lives of some of those sweet kids, dull the edges of others and pass unlodged through others, the newer classmates, or ones who were still floating above the earth, like I would have been at that age. She was the best suited person on earth to hold these myriad, individual reactions and follow up with the right amount of water for each child afterward and Stella unhesitatingly knew it.

Soon after our brief, mind-bending conversation, the Ativan took Stella away.

What do you dream about the first time you sleep after hearing you’re going to die?

This is meant to be no veiled indictment of Amy; I hold nothing but love for her during this time, truly, nor do I hold myself up for thinking we needed to tell her before we did. Amy wasn’t going to keep it from her forever, she just wasn’t ready; it was all in the timing for her. She was scared, it was her child, born of her; mine too, but a father has a different love than a mother, not deeper or more shallow, just different. Amy’s terror of losing her daughter was closer to the skin than mine, always would be, it was how she was built, nature. I don’t like saying that, makes me feel inadequate, broken … in deeper ways than I am now, but I AM less emotional than she is and far more rational, I don’t mind saying that.

During this time between January 27th and the day of truth telling, we’d been meeting with doctors periodically. Our radiologist had come up with a plan to ease some of the pressure in her pelvis with ten days of radiation. We tried; we managed 4 trips total. I don’t know how we kept the secret from Stella during this time. Like believing in Santa Claus, longer than her friends did, Stella had a way of knowing what to believe to keep herself safe … as if she didn’t want to end her childhood … as if she knew she would ONLY have childhood … in both the case, with Santa Claus and hearing her fate, she was controlling the voicing of the knowledge as much as we were.

I want to believe this.

We had tried the radiation plan, traveling to UW Medical and back each day, but Stella was as much drained by the motion of the ambulance and the nausea that ensued as the radiation seemed to give back. No amount of care, attention, not the right pillow nor perfect special avocado stuffy, not sweetness from the mothering, thoughtful, experienced radiation techs…nothing made up for the pain and nausea the short trip caused. And if the cancer was unstoppable, what was the point?

She just wanted to be home.

The next part I remember because I have photos that prompted me.

Later that night three teenage family friends gathered around her bed and tried to fit as many tiny rubber bands as possible in her short hair. This had been planned and the rubber bands retrieved by one of our dear friends. With her eyes closed tight she let Maile and Maire (Mora) make tiny bambam tufts all over her head. They murmured to each other quietly, easily, and giggled, as Maile and Maire worked on Stella’s hair. Jasper, two years older, sat in the chair by the bed staring at his friend as she lay there quietly. Her eyes were closed most of the time and this allowed him to stare. The room was dark, lights off, the only light coming from Amy’s lights and the various monitor lights on the many machines and the lights from the hall that worked around the curtain.

Stella was wearing my Stewart Lumber t-shirt, the bed covered in her soft owl blanket, boo her stuffy under her bruised hands.

Three teenagers in a room with the knowledge of their friend’s fate; their friend with knowledge of her own fate. They had heard the secret news from their parents earlier in the day that their friend was going to die; they’d also been told she now carried the truth. They did not speak a word of it together this night. Tomorrow her whole class would know. Then they too would be side by side with her, taking the struggle of moving into each next day, together.

It was bound to happen, the truth will out; and it finally had and now Stella could go into death on her own terms.

At this moment, as I sat with her and Amy and Charlotte in the gloaming hours of February 2nd, 2020, knowing she knew there was no 8th grade dance in her future, no first kiss, no volleyball victories, no playdates filled with ridiculous hilarity and screeching laughter with her friends, no more long hair, her only task was to lay in her bed, let her parents and friends tend to her… and, maybe this she didn’t know, keep getting brighter.

And she did. She did for all of us.

I didn't see the actual painting in this sharing until I read the last word. But the way you described it allowed my mind to paint it. Very powerful.

All love, all the time, Hans.